AI in Agriculture: A Look at Automated Vertical Farms

Swegreen's vision is to create a ‘Farming as a Service’ (FaaS), an in-store platform allowing supermarkets and restaurants to produce their own fresh produce autonomously

In February 2019, Swedish vertical farming firm Plantagon declared bankruptcy.

Since 2008, the company had sought to develop technology for industrial-scale food production in cities. But out of the ashes, something new arose: Swegreen, its effective successor.

The new company’s vision: to create a ‘Farming as a Service’ (FaaS), an in-store platform allowing supermarkets and restaurants to produce their own fresh produce autonomously.

By using artificial intelligence and digital monitoring to mimic nature indoors by controlling and optimizing factors like climate, nutrients, and temperature.

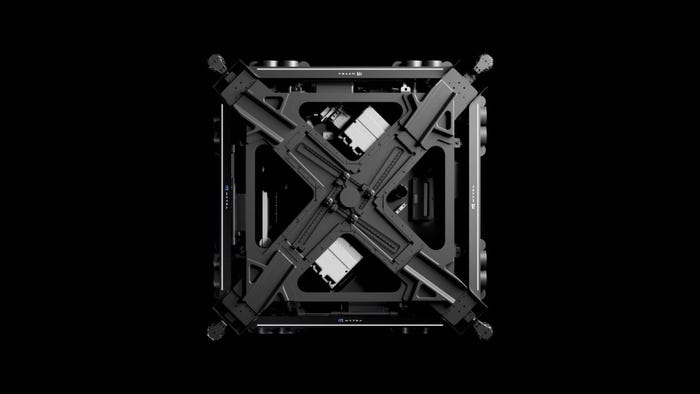

Swegreen’s indoor farms utilize IoT sensors as well as a digitalized control platform and AI-based cloud system that manages and optimizes the crops’ growth.

Inside the farms themselves, automated robot arms and elevators conduct the mechanical movements and prepare plants for the harvesting process.

For those that created Swegreen, the important thing was that the innovation that Plantagon failed to make fly, survive and advance to the next level, according to Sepehr Mousavi, chief innovation officer and co-founder of Swegreen.

Mousavi was the previous firm’s chief sustainability officer and is now part of the team hoping to take Swegreen forward and beyond.

He spoke to AI Business about Swegreen’s roots, AI’s place in vertical farming, and what lies ahead for his time.

Bringing Farming to the Edge

It didn’t take long for Swegreen to emerge after the collapse of Plantagon.

Mousavi said that his team would go on to bring in some “new blood” as well as some of the original investors and the key people in the competence team which already had separated way from the top management..

“The first proof of concept we started working on was a fully controlled environment farm under the The DN Tower (DN Newspaper) tower in Stockholm,” he said.

“There, we had enough competence, advanced technology and systemic thinking to control the environment and then to run a vertical farm, but also looking into the sustainability issues especially the integration of farms into host buildings.”

His team has since begun developing ideas on bringing such farms closer to the end consumer.

That was when the idea of FaaS as an in-store platform came about and would go on to became their business model innovation.

“For that to happen, we needed to become more digital and have a way of controlling these farms from distance,” he said.

“At the moment, we have a unique concept to produce inside the store from a seed to a fully grown plant. Some other firms do instore growing and sell Farming as a Service, but none of them are doing this in an automated setting with a control unit.

“The solution that we have is probably the most effective and efficient in terms of production when it comes to the number of units that we can produce on-site inside a supermarket.”

From Silicon Valley to Stockholm

When it comes to innovative companies, one could be forgiven for overlooking Sweden as a hotbed for innovation.

Silicon Valley is what most would likely imagine. But Stockholm? Less so, perhaps.

But Mousavi was firm that the work being done in his city is just as integral to what’s going on elsewhere.

“If you want to see where these technologies are the hottest, the U.S. is the biggest market for vertical farms and controlled environment agriculture. That’s thanks to early actors that acted there from the high-tech greenhouse industry. This is an extension of the greenhouse industry but with more focus on digitalization and space efficiency.

“Looking to Europe, the Netherlands has been a frontrunner in terms of the greenhouse industry. They have a national CO2 grid that takes everything from different factories and sends it to greenhouses. But Plantagon created a vertical farming market in Sweden back in 2010 when it wasn’t an industry. They were the pioneers of the market, together with the likes of AeroFarms and others.”

He said he had spoken to a Ph.D. researcher who is said to have found 14 different actors active in urban arable farming in Stockholm.

Mousavi outlined this small, but in his view, significant finding.

“It’s not a big city, with a population of around 1 million. In a Nordic sense, it’s the biggest city and dubbed the capital of Scandinavia, but Sweden has a big focus on innovation and tech. Sweden being a very small country, there are lots of tech companies. SweGreen had a good platform atop one of the pioneers in this space, and then the amount of focus that the Swedish consumers have on sustainability has also been a helping factor.”

He agreed that when looking at the level of funding in Silicon Valley, it’s not really comparable. “They’re playing in another league,” he said but suggested that in Europe, Stockholm has the highest number of unicorns per capita.

“There is a better potential for us by going international and it’s been a part of our strategy to go international,” he said.

“We definitely want a bigger piece of the pie. There is lots of room for improvement when it comes to automation and the use of robots which the US market is amazing for, and also the development you could have on the AI part.

“The American market is really interesting for us, and the competition is also high, but that’s why we’re trying to mature enough to be able to survive in a tough environment in the U.S.”

“There are already discussions if we could find at least one partnership with a good actor to be able to establish a showcase in the U.S.”

But it’s not just the U.S. market that Swegreen has its sights set on, but the Middle East as well, although more applying rather than developing there.

Competition? No, Collaborators

Upon looking at that U.S. market, Mousavi talked about some of the bigger players.

The likes of John Deere and Yanmar have all made strides into autonomous applications for farming, in the form of driverless tractors or crop cultivation equipment.

When asked about whether he feared the big players, he didn’t appear so.

“For them, I don’t think they’ll leave their core business. They’re not that agile to take over, but there are definitely some new business areas for in vertical farming.

“Many giants in this space aren’t looking to take over a niche market but be an enabler for the market and have a new business area. Like making sensors for vertical farming, or analytics, or robots. There are some European giants like ABB, Ericsson, and Siemens that are doing the same thing, to take niche innovations to the next step and for them to create a market.”

“I don’t see them as competition, but I see there might be a possibility for some interesting joint ventures for them to help us and then sell more machines.”

The Future is Green for Swegreen

Late last year, Swegreen secured over $1 million via an investment from Vinnova – the Swedish government’s innovation agency that administers state funding for R&D and more than $2 million in private equity.

But that was a year ago, and given Mousavi and Co’s plans to take its tech to places like the U.S., what does the future hold for Swegreen?

“We need to have enough financial capacity in order to move towards the visions that we have,” he said.

“We have defined visions for different parts of our innovation both hardware and software wise. R&D needs R&D infrastructure and human resources. This depends on how good a VC we find who wants to be a part of this journey and could give us a fair price based on the valuation that we have.

“Next year for us is fixing some small bugs, but we have a plan and a scalable solution and an innovative vision.”

The vertical farming space is expected to be worth $9.7 billion by 2026, according to MarketsandMarkets.

Mousavi and his team at Swegreen have the passion and an innovative idea. However, in order to revolutionize how produce is grown, they will need plenty of financial support, and perhaps just a little bit of luck.

This article first appeared in IoT World Today’s sister publication AI Business.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=100&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=400&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)