Hobbyist drones may be all the rage, but they could also pose serious security risks and also change the face of modern warfare.

February 9, 2017

During the Super Bowl halftime, a swarm of some 300 glowing drones accompanied Lady Gaga’s halftime performance as she started singing “God Bless America” and segued into “This Land Is Your Land.” As the pop star intoned the verse, “Through the night with the light from above,” a constellation of Intel’s Shooting Star drones twinkled ahead, later forming the image of an American flag.

But as much as the drones wowed the audience, the segment was not live. The Federal Aviation Administration declared that the airspace surrounding the stadium—34.5 miles in all directions—was a “no drone zone.” The Lady Gaga–drone segment was filmed beforehand.

“Drones are becoming much more popular, but they also pose certain safety risks,” explained FAA Administrator Michael Huerta in a statement.

Indeed they do. There are already many accounts of people doing stupid things with drones. “Some people have no idea of what they are doing, or they just want cool footage and will fly a drone close to, say, a skyscraper in Manhattan,” says Ulrike Franke, a doctoral student and drone researcher at Oxford University.

Between August 2015 to January 2016, FAA counted 583 separate drone accidents. There is bound to be many more, now that there are already more drones registered in the U.S. than civilian aircraft—and drone registration only started last year.

Related: The 10 Most Vulnerable IoT Security Targets

Drone-related accidents have already caused significant injuries. There is the drone that sliced a toddler’s eyeball in England in 2015. And then there is a photographer at a TGI Friday’s in New York who had the tip of his nose sliced off by a drone a year earlier.

Incidents like that, however, have been rare so far. Drones’ potential to cause injury, however, isn’t their biggest threat. Drones could cause significant problems in the airspace, and are becoming a weapon of choice for terrorists. As for the former, a drone could easily get sucked into a jet engine or crack an airplane’s windshield. Already, bird strikes cost the U.S. airline industry nearly $1 billion in repairs and flight delays annually and have caused more than 250 deaths since 1988. Drones, however, are much denser and have batteries containing volatile chemicals.

While researchers across the world are now crash-testing drones, unmanned aerial vehicles have already interfered with airlifting patients to hospitals and aerial firefighting.

Drones as Flying IEDs

Drones affixed with bombs could be a sort of flying version of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) or could launch chemical-weapon attacks. ISIS claims that its drones have already killed 14 people while wounding an additional 25, according to an infographic from the pro-ISIS Yaqeen Media organization. Hezbollah and the Taliban are also reportedly using drones for combat operations.

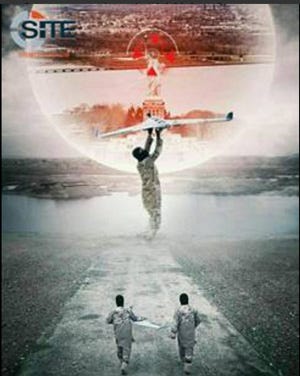

ISIS just published a video purportedly showing drones launching aerial assaults. Terrorist sympathizers have also released images showing a soldier launching a military drone aimed at the Statue of Liberty and U.S. Capitol, according to Rita Katz, director of SITE Intelligence Group.

Terrorist groups are deploying various unmanned flying vehicles, including off-the-shelf hobby drones carrying grenades and bespoke commercial drones.

Terrorist groups are deploying various unmanned flying vehicles, including off-the-shelf hobby drones carrying grenades and bespoke commercial drones.

Terrorists, however, won’t likely win wars with militarized drones alone. “It is a bit like the IED threat. It is not decisive. It also means that patrols will have to be much more careful and they will come up with anti-drone measures,” Ulrike Franke says.

A Controversial Weapon

In hindsight, it’s predictable that terrorists would begin to use drones to launch attacks. After all, the United States has used them for years to launch seemingly countless attacks on targets in the Muslim world, killing hundreds civilians in the process.

“The resentment created by American use of unmanned strikes … is much greater than the average American appreciates,” said the retired General Stanley McChrystal in a 2013 Reuters article. “They are hated on a visceral level, even by people who’ve never seen one or seen the effects of one,” added McChrystal, who had been the former ISAF commander in Afghanistan.

There is no confirmed number of deaths from these drone attacks, and it is impossible to tell how many of these deaths are civilians. The U.S. government’s numbers are substantially lower than estimates for organizations such as the Bureau for Investigative Journalism.

While drone attacks have been common for years, the debate around it in the United States didn’t start until the media reported that a drone strike killed an American citizen. In 2010, a drone strike targeted the American citizen Anwar Al-Awlaki in Yemen who hadn’t been charged with a crime but was thought to be an al-Qaeda mastermind. Two weeks later, the United States launched a separate drone attack that would kill Al-Awlaki’s 16-year-old son, Abdulrahman, his 17-year-old cousin, and other Yemeni citizens. President Trump recently authorized a drone strike that killed Al-Awlaki’s 8-year old daughter, according to Arabic media reports. During the Obama administration, such drone strikes prompted the ACLU to file litigation against the U.S. government.

Drones and the Future of Air Combat

Ultimately, drones seem poised to rule the skies. “The technology is very promising. You can do things with them that you can’t do with manned aircraft,” Franke says. Drones, for instance, could withstand super-strong G-forces that would cause a pilot to faint. And engineers would have much greater freedom when it comes to designing military drones.

Drones are also considerably less expensive than fighter jets, and it is simpler to train drone pilots than it is to train fighter pilots. It is, however, difficult to compare the two. “A Reaper drone and an F-35 are about as similar as a machine gun is to tank,” Franke notes. The low price tag of drones even prompted the U.S. state of North Dakota to legalize armed police drones.

As for the F-35, that jet has recently under fire for its high price tag. While an MQ-Reaper drone costs $14.75 million, the F-35 costs $94.6 million to $122.8 million, depending on the version. In general, drones costs substantially less than manned craft although the gap for strategic intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance craft is smaller.

As for the F-35, its high cost has helped fuel the narrative that the craft may be the last, or at least one of the last, manned fighter jets.

It may be premature, however, to make that assessment. The U.S. armed services plan on operating the F-35 until 2070, and modern military drone technology is still immature. “The drones that are out there are not super high tech,” Franke says.

The Coming Swarm of Military Drones

Ultimately, swarms of drones could be used in warfare — not just for eye candy at events like the Super Bowl. As a case in point, Air Force chief scientist Greg Zacharias told Scout Warrior magazine that F-35 pilots would be able to control small swarms of drones from the aircraft cockpit, using them for sensing, sensing, reconnaissance, and targeting functions. The Pentagon is also testing swarms of miniature Perdi drones that attack like a swarm of killer bees. There’s also the possibility of low-tech drone attacks. What if a hundreds of drones, flying in formation, were equipped with grenades?

“Militaries around the world are thinking about teams of manned and unmanned craft,” Franke explains.

While an air-to-air missile can bring down a solitary aircraft, it will be much more difficult to wipe out an entire swarm of drones. “If you go in with a swarm of 100 drones, and three get shot down, you still have a big swarm left,” Franke adds.

Ultimately, as artificial intelligence technology advances, swarms of autonomous drones could work together like a single organism to perform new types of military operations. “In the future, there may be flying minefields where hundreds of drones could join together to form a kill net,” Franke notes. “Or a network of drones could wait in reserve in a battle and rush in to help if needed.

For now, the public remains infatuated with drones. Last year, Gartner positioned the technology three-fourths of the way from the peak of its hype cycle. But as non-military drones become ever more common, so do the chances of serious drone-related accidents. “Maybe one person is killed from an off-the-shelf drone that you or I could get from Amazon, or maybe it is 300,” Franke explains. “But it could turn around public perception. It is impossible to regulate drones in a way that is 100% safe, so the question is: ‘how good are we at imagining what could happen?’”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)